THE LANGUAGE OF LOVE

Two trends in society and the Church empty the joyful impulse of love of its divine authenticity. Recognition is the first step to overcoming them

The English language is rich and robust but there are points at which it fails us. One perfect example is living with only word for love. The word has to be manipulated to shape feelings as diverse as loving a dress on sale in Zara to loving someone enough to marry them. The word is overused and has become debased. Without the deep texture afforded by a choice of words, love has become prey to some corrosive trends. Two in particular have diminished its divine character. The first is growing sentimentalism in society; the other is persistent legalism in the Church.

Creeping sentimentalism in society has been observed by a number of commentators, usually with a view to making political capital out of it. The suggestion is that the growing emphasis placed on emotion in public life has distorted our values. It is said, for instance, that public policy on a range of issues from humanitarian intervention to assisted suicide is at risk of being decided by the emotions which individual suffering provokes in those who witness it. There are dangers in allowing our feelings about specific cases to determine broader policies which can have many other unintended consequences. Humanitarian intervention in another country protects many innocent people whom we see suffering on our TV screens. The same intervention usually results in many other people being killed, some of them also innocent. Similarly, a law to permit assisted suicide may satisfy some who fear they will otherwise suffer deeply at the end of life, yet its provision may put at risk some of the most vulnerable people in our society: confused and depressed older people who do not want to be a burden on others.

Emotion alone is a poor basis for deciding policy, not least because mobs are swept up by prevailing moods which prove deeply unsympathetic to minority needs. However, emotion should have a place. Any society which does not give proper recognition to the role of emotion suppresses a cherished gift which makes us human. The new atheists speak at great length about the need for the world to be governed by purely rational thinking, but without the tempering of love, this can turn out to be cold, calculating and instrumental. Our reasoning powers are just as much at risk of being wrong as our emotions. We need the interplay of both to guide us through life.

The problem with the appeal to love lies in its vagueness today. What exactly do we mean by it? In his letter to the Romans, Paul says that the law is ‘summed up in this word: ‘love your neighbour as yourself’ (13:9). Yet this has been reduced today to nothing more than an ethic of tolerance. Tolerance has become the supreme virtue, but it is wholly inadequate in building community. GK Chesterton said that ‘tolerance is all that is left when love runs out’. He said this long before tolerance became the spirit of the age and it is as if he prophesied how we would view one another at the start of the twenty first century in a society where fewer people love the stranger.

On reason people stumble over the path Jesus lays before us when he says we should love our neighbour as ourselves is the assumption that this love should be a warm and fuzzy feeling towards people. That’s what we feel when we like someone. Loving someone is a much deeper commitment: it means doing the right thing by them. God is looking for the right behaviour, not the right feelings.

If society has become too sentimental and unsure about what it means to show love to others, the Church may have a very different problem. This is the way legalism can choke love like a pernicious weed wrapped around a precious flower. Churches stumble when they become rule-based in how they relate internally. To put this bluntly, it’s when we make a mistake and, instead of believing we will be forgiven, we suspect there will be a price to pay for our failure; some kind of punishment for slipping up.

When we make a mistake in church that might impact on someone else or we make changes within our powers that affect others, are we fearful of the outcome or confident that we will be well received by others? Churches where people are uncertain how they will be received when they slip up may have some way to go on their journey. A church which is full of love does not just bestow forgiveness, it goes out of its way to help people overcome the nagging guilt they can’t wrestle out of. To love someone as God intends does not mean we care for them just enough to forgive them and no more: it calls for us to lavish our acceptance and resources on them. Churches which praise people for making the effort in their work walk in the way of Christ more than those which criticise people for showing too much initiative.

My gut feeling is that our churches tolerate far too much that is not of God in their common life. In Matthew 18: 15-17, it speaks of a hard-edged accountability for sin, where people are compelled to face up to the hurt they have caused. This is the basis on which love and forgiveness are extended. Without this accountability, one to another, sin is allowed to fester and resentment grows from which we judge one another more harshly.

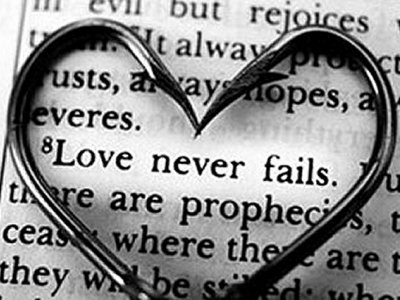

God’s love is not sentimental because it comprised a hard-headed decision to send his Son as a sacrifice for human sin. There is nothing fuzzy about this: its outline is bold and stark. And neither is this love legalistic. He does not judge us by our failings but pours grace over us which overwhelms our guilt and fear with waves of joy and peace.

What is love? God is love. There really is only one word for love after all.

POPULAR ARTICLES

Obama's Covert Wars

The use of drones is going to change warfare out of all recognition in the next decades.

Through A Glass Starkly

Images of traumatic incidents caught on mobile phone can be put to remarkable effect.

What Are British Values?

Is there a British identity and if so, what has shaped the values and institutions that form it?